COVID | Credit | Economics & Growth | Equities | Monetary Policy & Inflation

COVID | Credit | Economics & Growth | Equities | Monetary Policy & Inflation

Bad news related to the outbreak of the Novel Coronavirus, COVID19, is unlikely to be fully priced in. Yet over the next few months, I still expect TINA (There Is No Alternative) to remain the prevailing market regime.

Equity Markets Have so Far Shrugged off Coronavirus Concerns

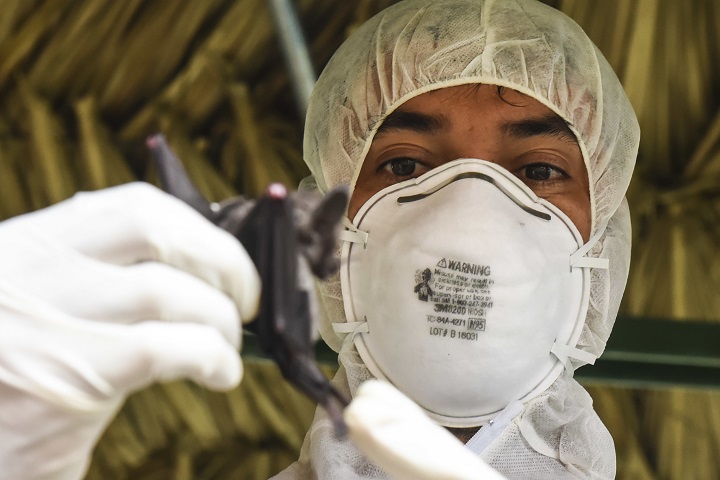

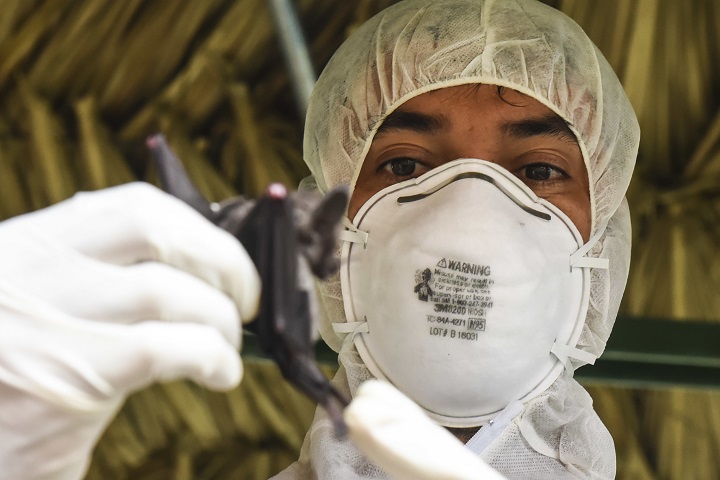

Equity markets’ resiliency to COVID19 could reflect expectations of early containment of the epidemic or of limited impact. But the former, at least, appears unlikely. COVID19 is spreading faster than either SARS or the Swine Flu (Chart 1). In addition, there are doubts on the numbers reported by China, and contagion chains without a direct link to China have already appeared – for instance in Singapore. So at this stage, a global pandemic seems more likely than not.

This article is only available to Macro Hive subscribers. Sign-up to receive world-class macro analysis with a daily curated newsletter, podcast, original content from award-winning researchers, cross market strategy, equity insights, trade ideas, crypto flow frameworks, academic paper summaries, explanation and analysis of market-moving events, community investor chat room, and more.

Bad news related to the outbreak of the Novel Coronavirus, COVID19, is unlikely to be fully priced in. Yet over the next few months, I still expect TINA (There Is No Alternative) to remain the prevailing market regime.

Equity markets’ resiliency to COVID19 could reflect expectations of early containment of the epidemic or of limited impact. But the former, at least, appears unlikely. COVID19 is spreading faster than either SARS or the Swine Flu (Chart 1). In addition, there are doubts on the numbers reported by China, and contagion chains without a direct link to China have already appeared – for instance in Singapore. So at this stage, a global pandemic seems more likely than not.

Market pricing could still be justified if the financial consequences of a global pandemic are limited. A combination of low bond yields, mediocre but reliable growth, underperforming inflation, and Fed put supports a TINA bid for equities, even at historically unattractive valuations. Under TINA, investors buy bonds for capital gains and equities for income.

The two main risks to TINA could be inflation and credit deterioration. A sustained spike in inflation would prevent the Fed from easing and lead to higher bond yields and a bear market. However, this appears unlikely based on the recent experience with tariff increases. Average tariffs on US imports increased from about 2% to about 4% during 2018-19. Yet the impact on core goods inflation has been limited (Chart 2), which in my view reflects the mutually reinforcing, weak market power of businesses and workers.

Of course, if global factory shutdowns bring about pervasive input shortages, cost pressures caused by COVID19 would be stronger than under the 2018-19 tariffs. But even if firms raised prices to reflect these shortages, due to workers’ weak bargaining power, higher prices would bring about lower real wages. This would lower demand for firms’ products, which in turn would restrain their ability to raise prices. The development of a wage price spiral, necessary for a sustained pickup in inflation, appears unlikely.

Credit deterioration appears a more likely contender to end TINA, though at this stage this is not my base case. In this scenario, due to falling demand and input shortages, a large number of firms would lose the ability to service their debts to the extent that they would have to lay off workers. Fed easing would only have a limited impact on growth due to weak balance sheets for corporates and low-income households. Investors would become concerned over capital losses and move into bonds.

This scenario would require deep demand and supply shocks that, at this stage, appear unlikely. The US economy is slowing but at a gradual pace. It remains largely domestic-driven: no post-WWII recession has been driven by an external demand shock.

Additionally, previous high mortality episodes have not been associated with deep recessions. For instance, in the US during 1918-19, the Spanish Flu (which has a higher mortality rate than COVID19) caused at least 675,000 deaths, about 0.6% of the population. While this dented growth, it did not drive the 1918-19 recession, largely caused by the end of the war boom. Similarly, in Russia during the first half of the 1990s life expectancy decreased from 70 to 65 years, which led to 1.6 million excess deaths or about 1% of the Russian population, disproportionately working age males. This is estimated to have detracted about 30 bp from GDP growth.

Of course, since 1918 the global economy has become much more interdependent. At the same time business contingency planning, the ability of many service workers to work remotely, the development of e-commerce, stronger health systems, and advancements in science have greatly increased economic resiliency to large-scale epidemics.

For COVID19 to bring about a deep recession in the US, a large-scale panic would be required. Workers not showing up to work, consumers avoiding public spaces, or employers shutting down plants would bring the economy to a standstill. The risk of panic could be higher this time around than in previous high mortality events because social media could act as facilitators.

A panic is not my base case scenario, though I suspect markets are likely to be surprised by the hit to exports and manufacturing. I will be watching closely end-February/early March data to get a sense of the hit to confidence (business and consumer surveys, core capital goods); of the extent of input shortages (ISM manufacturing); and of changes in financial fragility (bankruptcy filings, NACM (National Association of Credit Managers) index). Over the longer run, with credit deterioration the biggest risk to TINA, the more reliable leading indicators of TINA’s demise could be corporate bond spreads, especially high yield (Chart 3).

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.