What Is Market Monetarism?

- Market monetarism is a macroeconomic theory that proposes central banks use nominal GDP targeting to stabilize nominal incomes.

- This type of monetary policy targeting is novel: most central banks use inflation targeting.

- The market monetarist school builds on Milton Friedman’s monetarism, but withdraws from using monetary aggregates as an indicator of monetary policy stance. Instead, it looks more towards developments in financial markets.

Why Did Market Monetarism Flourish Post-GFC?

Danish economist Lars Christensen coined market monetarism in 2011, with economists Scott Sumner and David Beckworth promoting the idea. The theory became popular following the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), as economists began to link the severity of the Great Recession to the tight monetary stance of central banks.

Why? Traditionally, central banks use the interest rate, or policy rate, to respond to changes in inflation and output. During a recession, inflation-targeting policymakers will reduce the policy rate to stimulate spending, with the aim of bringing inflation back to its target and growth back to its potential.

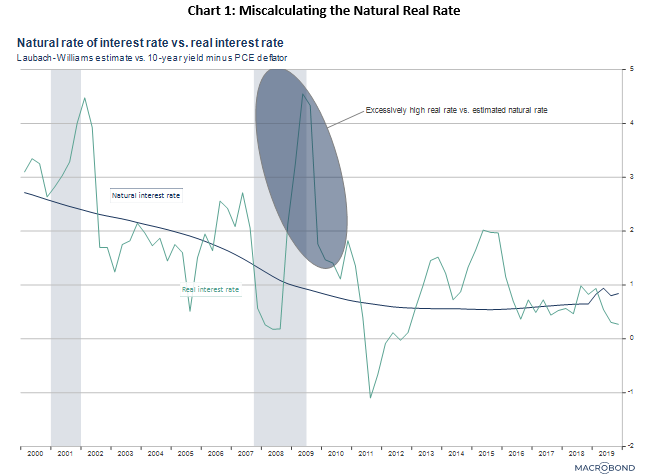

This framework, however, hinges crucially on central bankers’ estimate of the natural real interest rate – the rate that keeps the economy at full capacity – and the actual real interest rate in the economy (nominal interest rate minus inflation). If the natural rate is below the real interest rate, which it appeared to be before and during the GFC, then monetary policy is contractionary, and the economy slows (Chart 1).

The challenge, therefore, is finding the natural real rate. A key ingredient of the natural rate, potential GDP, is notoriously hard to measure. And the GFC was a prime example of where policymakers ‘missed the drop’ – they overestimated the natural rate. Effectively, monetary policy was too tight, which led to higher unemployment and lower inflation.

However, even if policymakers had correctly calculated the natural real rate, they may still have been prone to measurement errors: inflation targeting also relies on accurate estimates of inflation and real GDP – both hard to gauge in real time. And there is ample evidence that the natural rate might even be lower than what traditional estimates like the Laubach-Williams suggest.

Instead, market monetarism advocates using nominal GDP targeting. It reduces the variables a central bank must track to just one – the sum of all nominal spending in the economy. It also eliminates the need to control real variables that are largely determined by economic factors outside monetary policy. And combined, it minimizes measurement errors of where the economy is in real time, thereby avoiding the problem central bankers had around the GFC.

Friedman’s Monetarism: The Foundation for Market Monetarism

Market monetarism builds on the tenets of monetarism, a macroeconomic theory that Milton Friedman developed alongside Anna Schwartz. Monetarists argue that governments can control the amount of money in circulation (the money supply) to stabilise the economy. As the IMF states, the theory proposes that the money supply is the ‘chief determinant of GDP in the short run and inflation over longer periods.’

Friedman and Schwartz argued that the Fed’s policy of tight money, which it was pursuing because of the 1920s stock market bubble, led to the Great Depression. By restricting the money supply, the Fed effectively strangled demand in the US.

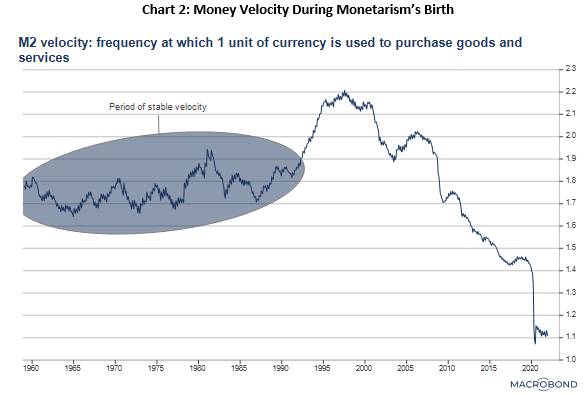

How? It comes down to the Quantity Theory of Money, which is central to monetarism. This theory states that the money supply multiplied by velocity (the rate at which money changes hands) equals nominal income (the number of goods and services sold multiplied by the average price paid for them). Around the 1970s, when monetarism gained prominence, the velocity of money was stable (Chart 2). Therefore, changes in nominal income, which reflect changes in real demand and inflation, are largely a function of the money supply.

The argument was compelling at the time. Targeting the money supply helped the US (led by Fed Chairman Paul Volcker) and the UK (led by Prime Minister Margret Thatcher) combat high inflation during the 1970s and 1980s. Even as recently as 2008, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke increased the money supply to boost demand.

But the velocity of money is prone to large swings, especially during crises. Then, increasing the money supply may no longer increase nominal demand – the biggest critique of monetarism.

Market Monetarism vs Monetarism

Recognizing the flaws of targeting the money supply, market monetarists instead advocate for targeting nominal incomes. But money still matters – that is why ‘monetarism’ is still in the name.

To understand this, think of there being two goods in an economy – non-money goods and money goods. Here, money is a ‘good’ in that individuals demand money to purchase non-money goods, say a car. In a recession, there will be too many cars for the amount people are demanding: there is an excess supply of cars. In that case, there must also be an excess demand for money – people cannot get cars because there is not enough money. If nothing happens, nominal GDP falls.

To keep nominal GDP stable, central banks need to match this increase in money demand one-to-one with an increase in the money supply. In essence, the central banks step in to provide liquidity to support incomes so that people can purchase the same number of cars as they did before. That removes the excess supply of cars. The relationship between recessions and money is why Christensen tweaks Friedman’s famous line to say that a ‘recession is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon’.

How is this concept different from monetarism? Traditional monetarists believed monetary aggregates, like M1, were the best indicator of this balance between excess supply and demand. That is, whether monetary conditions were too tight or loose. However, the velocity of money component misled them. So instead, market monetarists focus on asset price changes as the best – indirect – indicator of the monetary policy stance. This is because we can generally view markets as efficient, containing useful information about the current and expected stance of monetary policy. That is why Christensen added ‘market’ onto ‘monetarism’.

What Are the Core Tenets of Market Monetarism?

- Central banks should target the level of nominal GDP.

- Financial markets give a real-time indication of the monetary policy stance.

- Nominal GDP targeting improves the speed at which central banks can respond to economic shocks.

- Interest rates are a poor indicator of the stance of monetary policy.

1. Nominal GDP Targeting

This is the most important tenet. A nominal GDP target is an aggregate demand stabilizer. It also has the advantage of allowing the central bank to implement a whatever-it-takes approach. If constrained by the zero-lower bound in interest rates, it can still significantly loosen policy. And in the face of overshooting, it can tighten it. Most importantly, though, it is transparent and easy to measure, making monetary policy credibility straightforward to judge. Credibility is important for expectations, which are also a core tenet of market monetarism.

2. Markets as a High-Frequency Indicator

The stock markets, foreign exchange markets, commodity markets and bond markets all matter in market monetarism. For example, if nominal GDP expectations were below the central bank’s policy objective, it may favour a looser monetary policy stance. In this situation, we would expect to see stock prices rise and the currency depreciate. As nominal GDP expectations increase, long-term rates should rise. But short-term rates might fall due to the liquidity effect.

Market monetarists also think that prediction markets could guide policymakers about market expectations of future nominal GDP growth. These markets tend to outperform expert opinion so would also immediately reflect whether a certain policy was contractionary.

Even better, the Fed could create a liquid nominal GDP futures market. The nominal GDP futures directly price market expectations for future nominal GDP growth. This would allow the Fed to target these nominal GDP futures and adjust the monetary base automatically to keep the price of the futures within a narrow band that would align with future nominal GDP growth of 5-6%, for example.

3. Long Variable Leads and Policy Effectiveness at the Zero-Lower Bound

Under inflation-targeting regimes, policymakers must measure potential output, real output and therefore also inflation. All come with measurement errors, hindering real-time policy decisions. Nominal GDP does not suffer from these. Injections of base money can instantly affect (i) the exchange rate, (ii) interest rates, (iii) stock markets, and (iv) expectations.

That is why market monetarism argues that monetary policy should always be the first resort when a negative demand shock hits the economy, even when interest rates are constrained at zero. This contrasts standard neo-Keynesian theory, which advocates for fiscal policy during the liquidity trap. The challenge with fiscal policy, however, is very large possible lag times. Market monetarism argues instead that nominal GDP targeting has long lead times, which work through the expectations channel. The speed and transparency of nominal GDP targeting induce this big expectations effect.

4. Interest Rates Are a Poor Indicator of the Monetary Policy Stance

Mainstream economists, especially New Keynesian ones, place interest rates at the core of monetary policy. If the interest rate is low, the monetary policy stance is loose. But market monetarists disagree. They think low interest rates generally signal that money has been tight. That is, the policy has been contractionary! Instead, they would see rising long-term bond yields as signalling the policy was expansionary – because rising yields often reflect rising inflation expectations.

Also, as mentioned, the effectiveness of lowering interest rates depends on the so-called natural rate. If the natural rate is falling faster than the policy rate, money will be too tight. That means the policy will not be expansionary. And so, we must assess monetary policy relative to the natural rate and market expectations. By failing to, a country could fall into the zero-interest rate trap, which, according to Milton Friedman, is what happened to Japan.

Do We Have a Real-World Application?

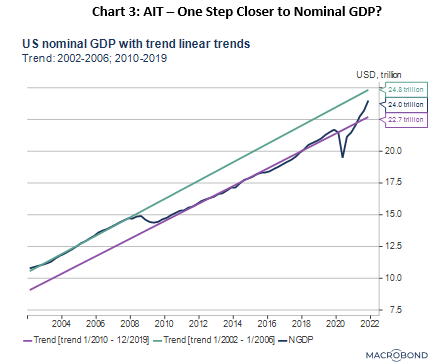

Nearly. Although different from market monetarism, the Fed moved to average inflation targeting during the Covid-19 pandemic. That let it boost demand differently from in past crises and similarly to a nominal-GDP-targeting regime. This led to a complete recovery in nominal GDP, which was not the case after the GFC when pre-2008 demand never materialised (Chart 3).

FAQ’s

→ What Is Nominal And Real GDP?

Nominal GDP is simply the measure of all the goods and services in a country over a set period of time. Nominal GDP is usually measured over a year or a quarter. Real GDP is nominal GDP when adjusted for inflation. Real GDP is generally thought to be a better indicator of a country’s economy.

→ How To Find Real GDP?

Real GDP is found by using the nominal GDP and then dividing it by the GDP deflator. The GDP deflator is the measure of how much the prices have increased since the last year. For example, if the deflator is at 1.05, then that is the figure that the GDP is divided by.

→ What is Gross Domestic Product?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the total value of all the goods and services that are produced by the country during a specific period. Usually, GDP is presented in the annual format, although quarterly GDP is also used quite often.

→ How Does Gross Domestic Product Differ From Gross National Product?

Gross Domestic Product is the value of the total goods and services that are produced in the country. Gross National Product, on the other hand, measures all the services and goods that are produced by the country’s citizens, regardless of whether or not they were produced within the country.

→ Does Nominal GDP Include Inflation?

Nominal GDP does not include inflation. Real GDP does include inflation, and it is calculated by dividing the nominal GDP by the GDP deflator (which is basically inflation).