Asia | China | Economics & Growth

Asia | China | Economics & Growth

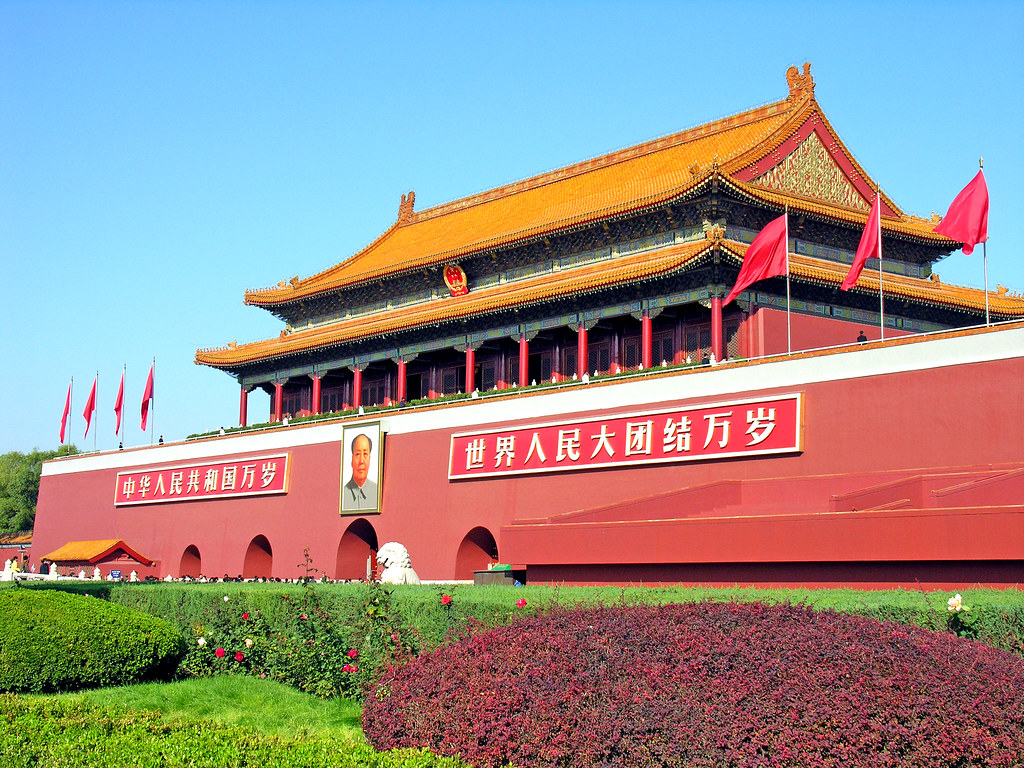

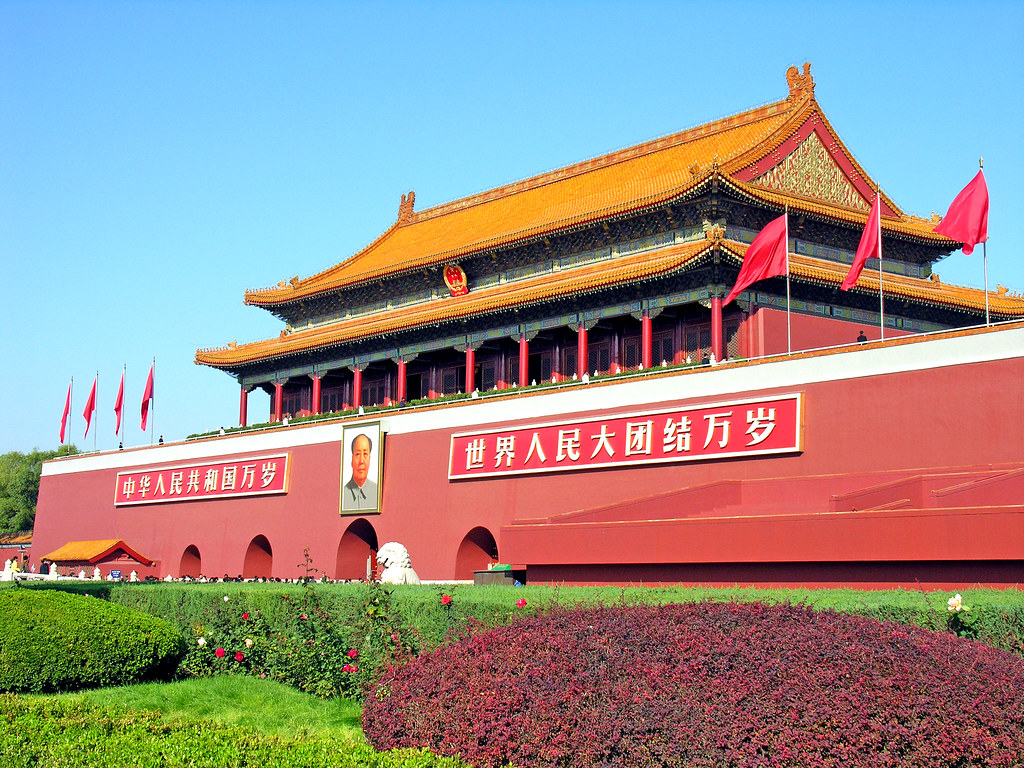

While much of the world is in freefall, activity in China is rebounding. This disconnect looks set to continue for now, with new cases of COVID-19 in China fairly small and its economy gradually reopening. By contrast, case counts are sharply rising and lockdowns occurring in many of the world’s largest economies. But far from being insulated from a global recession, China’s economy remains reliant on global demand, leaving it neither a safe haven nor a saviour for the global economy.

This article is only available to Macro Hive subscribers. Sign-up to receive world-class macro analysis with a daily curated newsletter, podcast, original content from award-winning researchers, cross market strategy, equity insights, trade ideas, crypto flow frameworks, academic paper summaries, explanation and analysis of market-moving events, community investor chat room, and more.

While much of the world is in freefall, activity in China is rebounding. This disconnect looks set to continue for now, with new cases of COVID-19 in China fairly small and its economy gradually reopening. By contrast, case counts are sharply rising and lockdowns occurring in many of the world’s largest economies. But far from being insulated from a global recession, China’s economy remains reliant on global demand, leaving it neither a safe haven nor a saviour for the global economy.

The disconnect across this week’s PMI data is stark. Manufacturing activity improved sharply in China after the historic low recorded in February, while for Europe output dropped to its lowest level in more than seven years, with worse still to come once services sector data becomes available. The same is true in the US where a modest decline in the ISM is yet to reflect the extent of the economic weakness in manufacturing, or indeed the cratering of activity in the service sector.

Forward-looking components on new orders and employment declined sharply in many of the March PMIs. Moreover, the longer supplier delivery times reflect disruptions in supply chains rather than the assumed higher demand that has artificially boosted headline readings (supplier delivery times account for 15% of the headline PMI index and are factored in as 100 minus the reported level). More telling is that production in Europe fell at its fastest rate in more than a decade, and this is set to significantly worsen. Disruptive containment measures were mostly announced during or after the surveys were done (except for Italy, where the PMI drop was larger), leaving April readings likely to record even larger falls.

Chinese activity data may be at odds with that elsewhere in the world for now, but a worsening global malaise will start to take its toll. We disagree with the thesis that China’s economy, driven by domestic demand, will insulate it from the global recession. Or that it will help put a floor under the extent of the global decline.

China’s presumed resilience to global weakness is that net exports have, on average, contributed zero to economic growth during the past six years. Consumption at over 60% of the economy has instead been by far the main driver of GDP growth. But while that may be accurate from a purely national accounts perspective, this assumes that any sharp drop in global demand, and as a result Chinese exports, is offset by a corresponding drop in imports. It is also at odds with the fact that manufacturing activity (and very likely employment), still account for more than one third of the economy and would suffer from any protracted drop in export demand. And trade itself accounts for around 40% of GDP.

Note: Feb / Mar PMI data excluded due to high volatility

China’s additional ‘buffer’ from its high savings rate is also unlikely to come to the rescue and prop up spending once weaker global demand hits the domestic economy. High national savings (around 45% of GDP, of which 23% of GDP is households) are more a reflection of the lack of social safety net in China. Given the health crisis and probably increased concern over job security, a structural shift that meaningfully moves savings lower seems unlikely.

On top of this, household debt in China may be low by advanced economy standards, but it has risen rapidly in the past decade. At just over 50% of GDP, it is above the emerging market average and is up from around 20% of GDP in 2008. So, in addition to high savings, debt service will act as a further constraint on consumption growth.

GDP growth forecasts are moving fast, and it is difficult to generalise on the relative size of forecast revisions for China compared with the rest of the world. But China’s dominance in global supply chains means that ultimately all forecasts are linked. China’s extreme lockdowns may mean it achieves what initially looks like a short, sharp(ish) recovery. But this is unlikely to last.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.