Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

Monetary Policy & Inflation | US

In the presser and minutes of the December meeting, the Federal Reserve (Fed) communicated that quantitative tightening (QT) will start this year. But to know why that is important and what it means for the economy, we must first understand the Fed balance sheet.

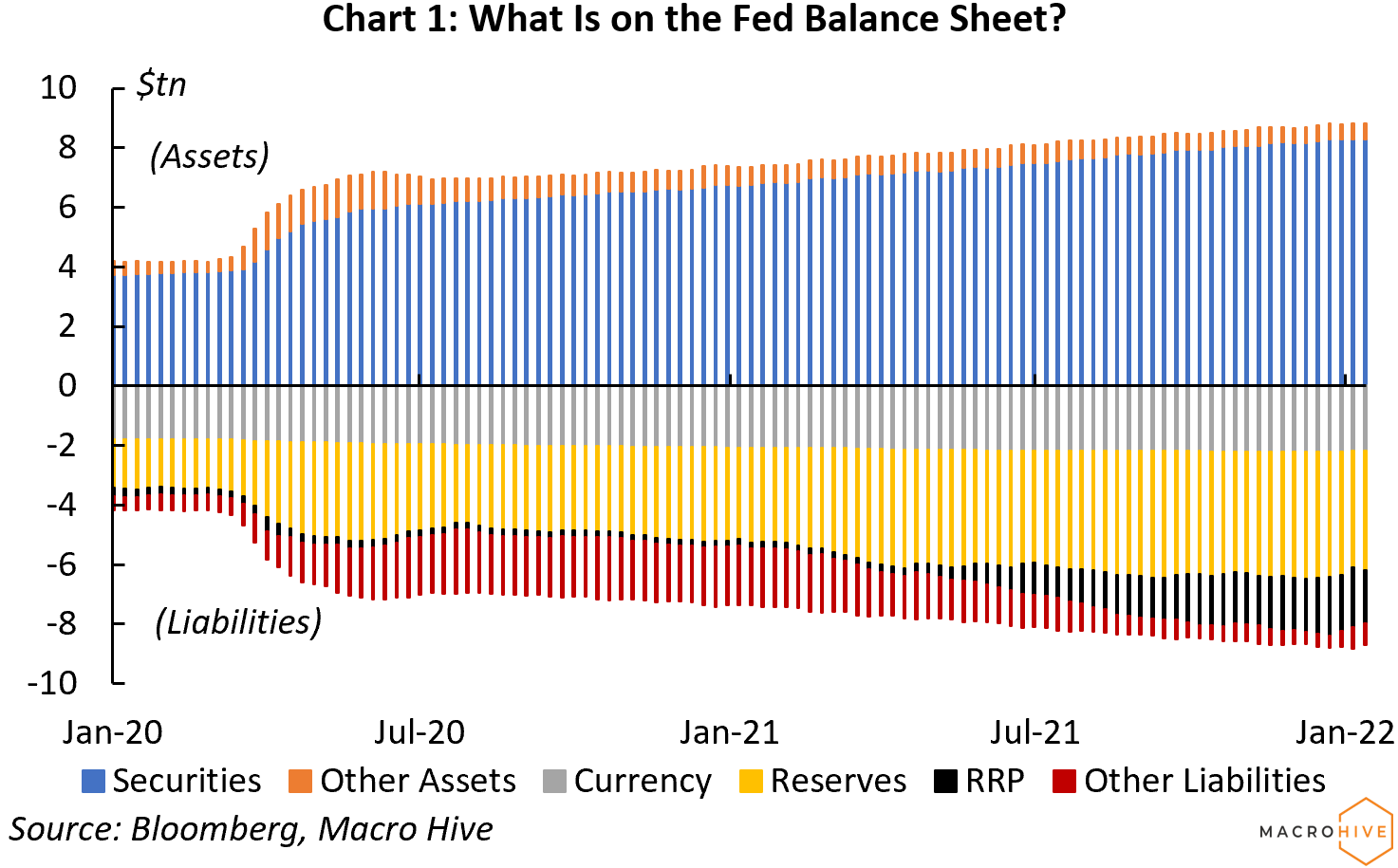

The balance sheet is a list of all the assets and liabilities held by the Fed (Chart 1). The Fed publishes a weekly balance sheet here (helpfully, Table 5 of the balance sheet release is a consolidated version).

Securities account for 95% of the total assets held by the Fed. The rest of the assets are various loans, the value of Fed buildings, etc.

At the outset of the pandemic, the Fed cut the policy rate to zero and engaged in quantitative easing. That is, it bought securities. From the end of February 2020 to early January 2022, the Fed balance sheet more than doubled to $8.7tn (about 37% of US GDP) on the back of an increase in the securities portfolio from $3.8tn to $8.3tn.

To fund these purchases, the Fed issued liabilities. As Chart 1 shows, it issues three main types: physical banknotes, reserves, and reverse repurchase agreements (RRP, known as reverse repos).

Physical banknotes represent about 25% of the liabilities, which the Fed calls ‘Federal Reserve notes’. This is the paper currency of the US, that is, dollar bills.

The Federal Reserve note item is always growing, irrespective of Fed policy or what is happening on other parts of the balance sheet. This is because in many countries, dollar bank notes are what people use when they do not trust the value of their own currency (or want to keep their transactions off the radar screen).

The Fed is happy to supply banknotes because they are the best deal ever: all it needs to do is to pay for the cost of printing them, and then it can use the banknotes to buy whatever it wishes. For instance, it can purchase the securities on the asset side of its balance sheet. And, of course, the Fed does not have to pay interest on banknotes.

Reserves represent about 50% of liabilities on the balance sheet. The Fed calls these ‘other deposits held by depository institutions’. That is a complex way of saying that these are banks’ deposits at the Fed –banks like commercial banks, savings banks, savings and loan associations, and so on. Banks need those to carry out banking business, especially to transact with the Fed or with other banks, pay their taxes, or meet regulatory requirements.

Since March 2020, banks are no longer required to hold a set minimum quantity of reserves. In practice, however, US bank supervisors strongly encourage them to hold substantial reserves as part of the large portfolio of safe assets they have been required to hold since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. The remuneration on the reserves, known as the interest on reserves (IOR), is currently 15 basis points (0.15%).

RRPs represent about 20% of total liabilities. RRPs differ from reserves in three key respects.

First, in exchange for depositing money at the Fed, RRP lenders get securities. RRPs are the reverse of Repurchase Agreements (RP, also called repos), where borrowers sell a security to their lender, typically overnight, with a promise to repurchase it back at a higher price. That difference in price is the implicit interest rate on the RP. So, RRPs are in effect collateralized lending.

Second, most Fed RRP participants are money market funds (MMF) and government sponsored enterprises (GSE) that either are ineligible for the Fed deposit facility or, if they are eligible, do not get paid interest. Consequently, the interest rate the Fed pays on RRPs is only 5bp (0.05%), lower than the interest paid on reserves.

Third, the RRP expansion is recent: it only started in April this year.

There are also other Fed liabilities, which represent about 5% of the total.

Having expanded the balance sheet on such a massive scale, there are two main reasons the Fed may want to shrink it.

First, the Fed wants to signal its inflation-fighting chops. While the Fed does not subscribe to the quantity theory of money (it believes spare capacity drives inflation), it likely sees a decline in the size of its balance sheet as signalling its ability and willingness to curb inflation.

Second, it wants to lower interest payments entailed by its forthcoming hiking cycle. The Fed could be concerned by the size of the interest payments it will have to make to banks as it tightens policy. In 2018, the Fed Funds rate (the interest rate at which banks lend excess reserves to one another overnight) peaked at 2.25%/2.5%. At that time, the Fed’s interest payments to banks represented nearly $40bn, up from less than $10bn when the Fed Funds rate was at zero (Table 1).

These payments, which lowered the Fed remittances to the Treasury, turned out to be politically contentious. This was a key reason to proceed with shrinking the balance sheet in 2017 – the first time the Fed conducted QT. This time, because reserves are over twice as high as in 2018, with the Fed expecting the terminal rate at 2.5%, interest payments could again turn substantial unless the balance sheet shrinks.

The Fed’s decision to engage in quantitative easing has significant consequences for investors. In particular, it could be negative for risk assets. To find out what quantitative tightening might look like in 2022, click here.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.