What Is the SWIFT Payment System?

- SWIFT is a messaging system used to facilitate cross-border payments. This means exporters of Russian goods and Russian importers of foreign goods are exposed to it.

- So far, EU and US actions have sought to minimize the effect on Russian energy exports and have avoided removing most Russian banks (by assets). But that has not stopped refineries and traders looking to avoid Russian oil.

- Russia was threatened with removal in 2014. Since then, it has created its own alternative. However, take-up is comparatively low, and few foreign counterparties use it.

- Excluding Russia from SWIFT will hit Russia and its trade partners by making the transfer of money, and therefore the trade in goods, much more difficult. While Russia is a small economy as a proportion of the world, it is a large exporter of goods.

A Background to SWIFT

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) is a communication platform started in 1977 in Belgium. Banks, brokerages and other financial institutions use it to facilitate cross-border money transfers.

Say a German company buys Russian gas. It transfers money from a German bank to the Russian gas company’s Russian bank by entering the recipient’s account number and SWIFT code. SWIFT sees heavy use for foreign exchange settlement and trade finance.

In 2012, Iranian banks were removed from SWIFT. SWIFT adheres to Belgian and EU law, not US law. But it is widely understood that the US can twist its arm to remove members – as it did with Iran.

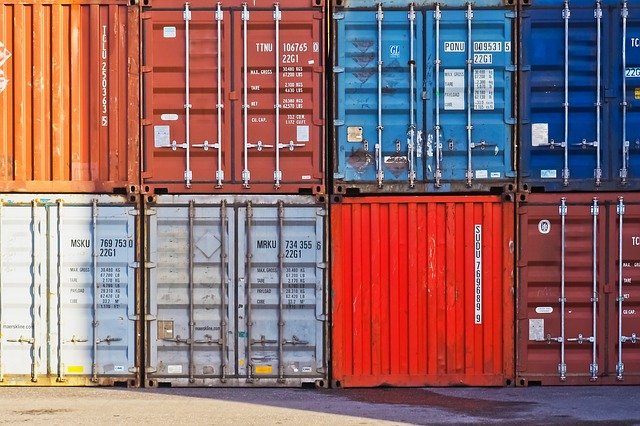

Currently, several Russian banks have been removed from SWIFT. They include VTB, Otkritie, Rossiya, Novikom (Rostec), Sovcom, VEB.RF and Promsvyazbank. While sanctions have gone further to target other banks, the banks removed from SWIFT represent the minority of Russian bank assets (Chart 1). The action appears designed to minimise the impact on Russian energy exports where possible.

Russia and SWIFT

Russian access to SWIFT lets it do electronic business with banks and companies in other countries. It thereby allows Russian exporters to receive payment for selling their goods abroad and for Russian importers to pay for goods.

Enjoying this Explainer? Sign up to our free newsletter for more.

SWIFT’s 291 Russian members represent 1.5% of flows – estimated to be around $800bn-worth of payments per year. Importantly, around 80% of Russian financial institution foreign exchange transactions occur in USD.

Can Russia Operate Without SWIFT?

Back in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, exclusion from SWIFT was touted as a possible extension to the sanctions. Former Russia Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin estimated then that losing SWIFT access could cost the Russian economy 5% of GDP. Since then, Russia has been working on its own domestic system for financial communication (SPFS).

By February 2020, there were 400 Russian banks on SPFS, more than that on SWIFT. Further, SPFS handled 20% of all Russian domestic financial communications at that time. However, SPFS has several shortcomings including high transaction costs and operations being limited to weekdays and working hours. Connectivity outside Russia is also limited.

As of the end of 2020, 23 foreign banks from Armenia, Belarus, Germany, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Switzerland were connected to SPFS. But only 12 reportedly used it. And reports indicate the Chinese government has not encouraged Chinese banks to join it, with the Bank of China the only Chinese member. The Russian government has previously been in talks to extend it to Turkey and Iran and integrate it with China’s own CIPS alternative.

Experience shows that companies and banks have been reluctant to do business outside SWIFT and outside the remit of US authorities, even when it is legal. For instance, in 2019 when the EU set up a special purpose vehicle, the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX), to support European non-dollar trade with Iran, take up and use was minimal.

Institutional discomfort with buying from the ultimate target nation of sanctions, despite the legality, could compound the effect that SWIFT’s removal has upon Russian exports. For instance, with regards to Russian energy, the US and EU have so far actively avoided targeting it too much, yet there are already reports of self-imposed embargos by traders and refiners looking to distance themselves from Russian energy.

The Potential Effects of Losing SWIFT for Russia

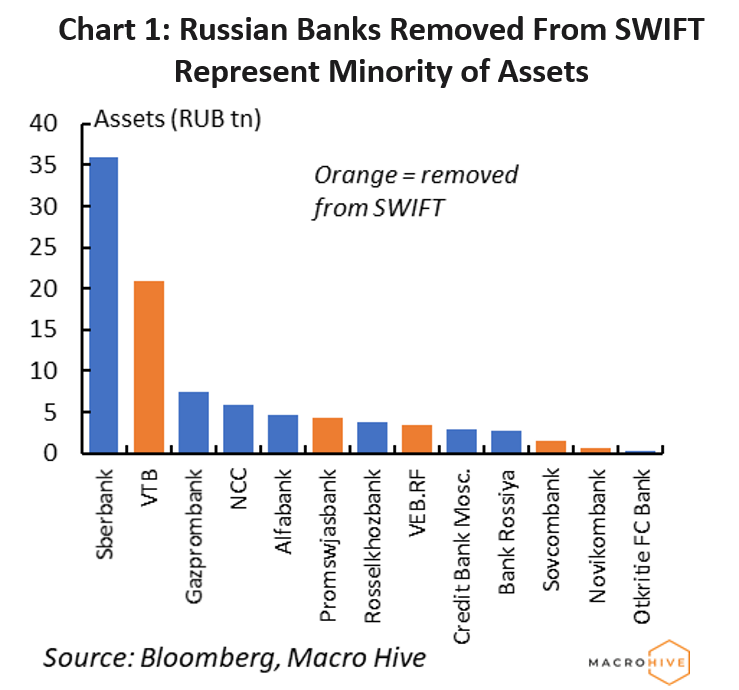

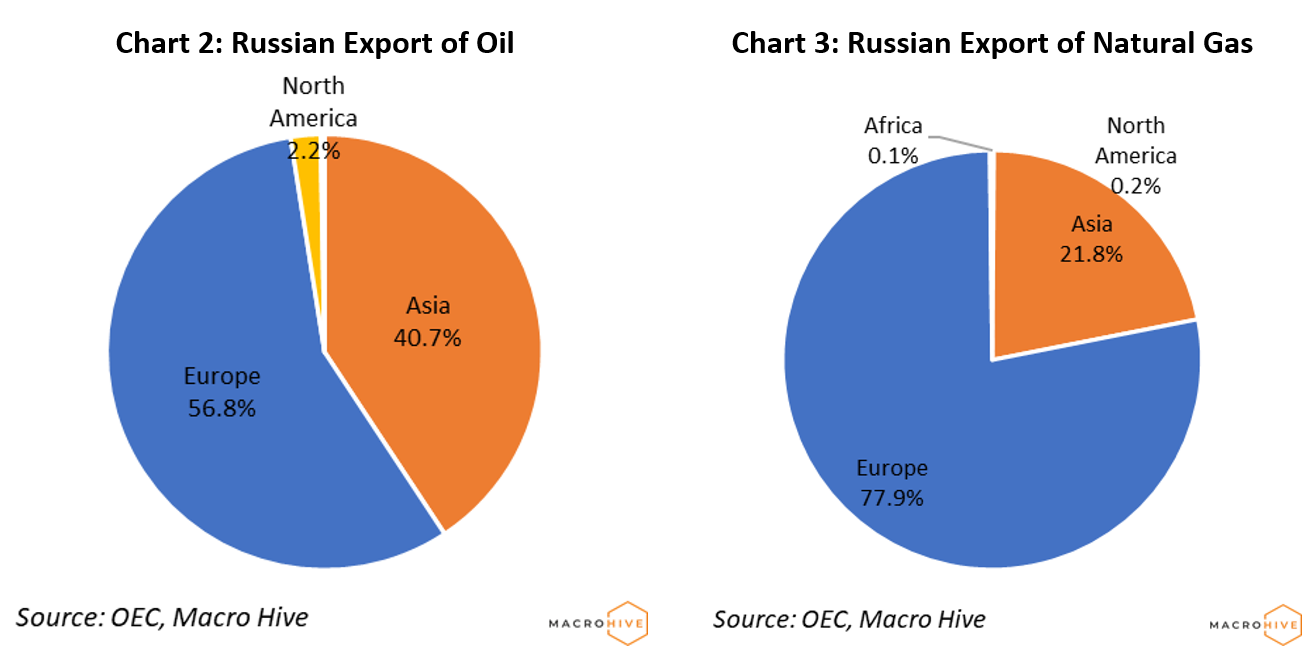

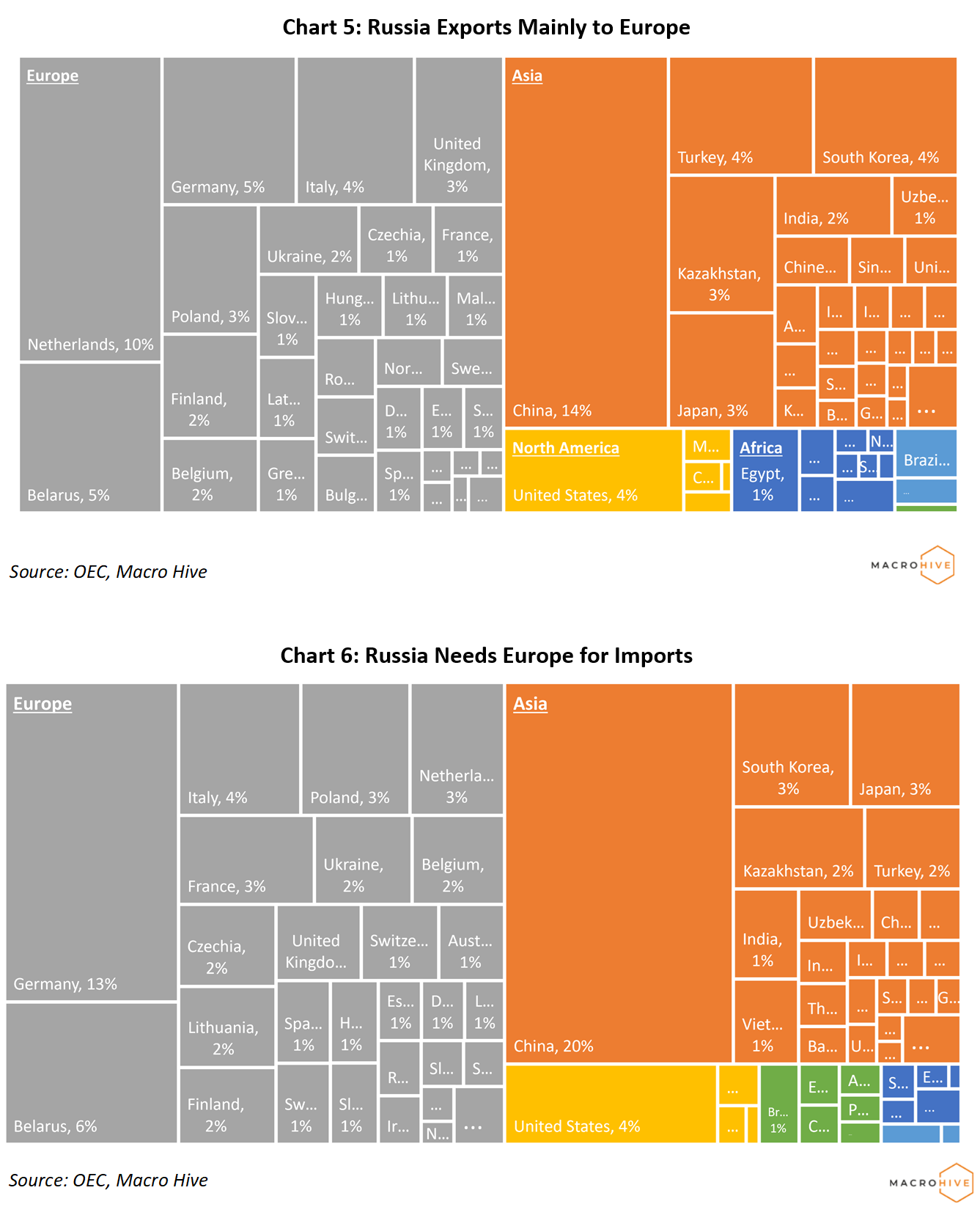

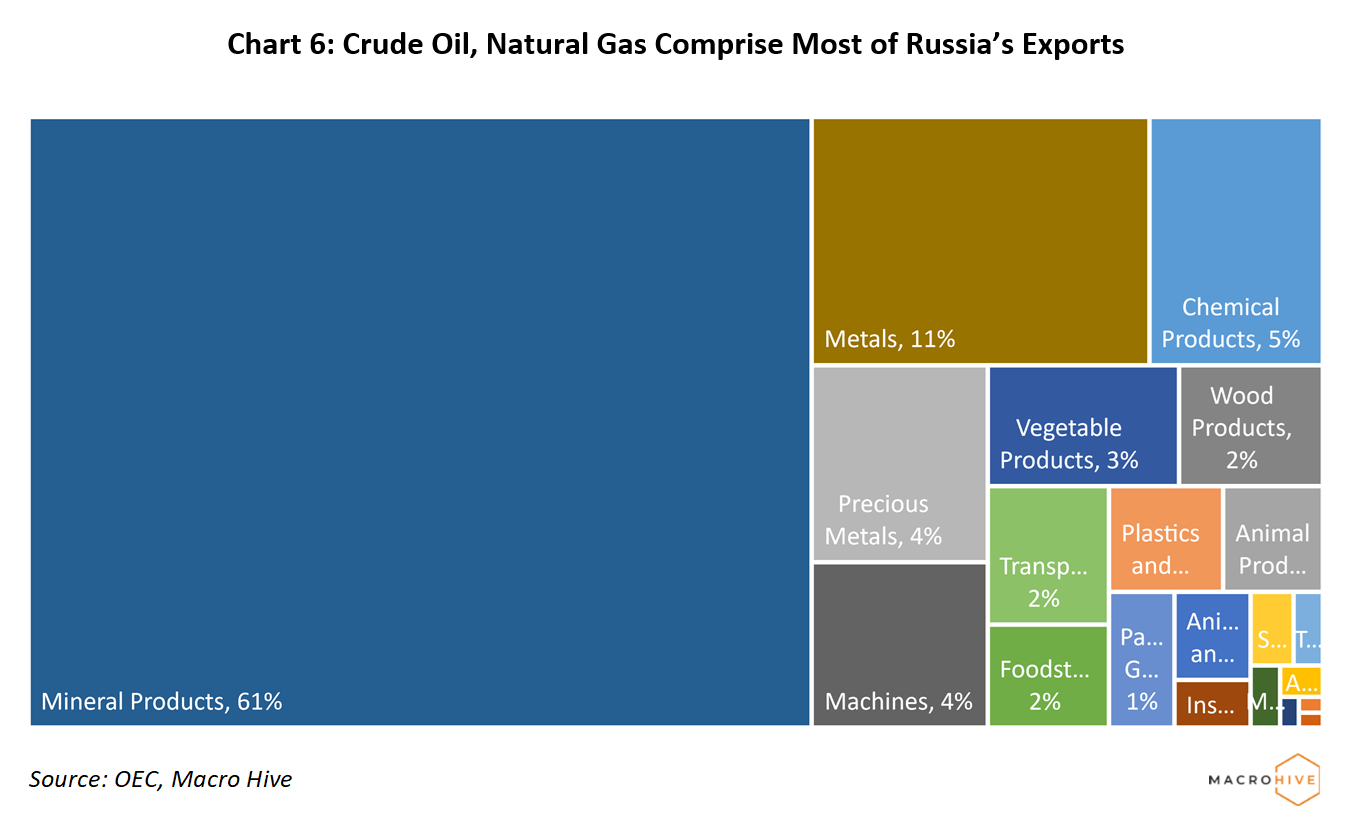

Cutting Russia out of SWIFT would primarily disrupt Russia’s ability to receive payment for international trade. Russia’s economy depends greatly on exporting commodities, particularly oil and natural gas, most of which goes to Europe (Charts 2 and 3).

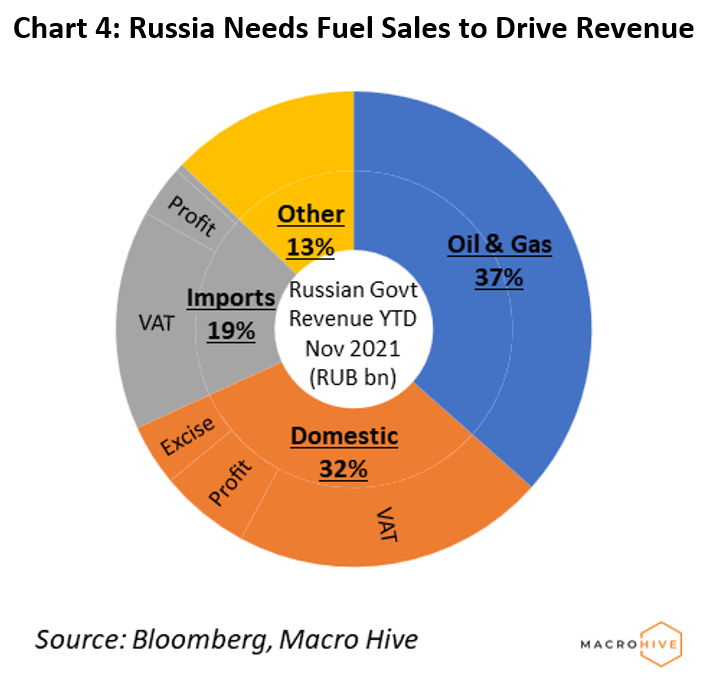

Further, the sale of oil and gas is also highly important for the Russian government. Oil and gas revenues accounted for over 35% of Russian government revenue in 2021 up to November, with imports accounting for another 20% (Chart 4).

Effects for the Rest of the World

Restricting cross-border trade is a double-edged sword. Not only is Europe the largest export destination for Russian goods, but it is also the largest source of Russia’s imports (Charts 4 and 5).

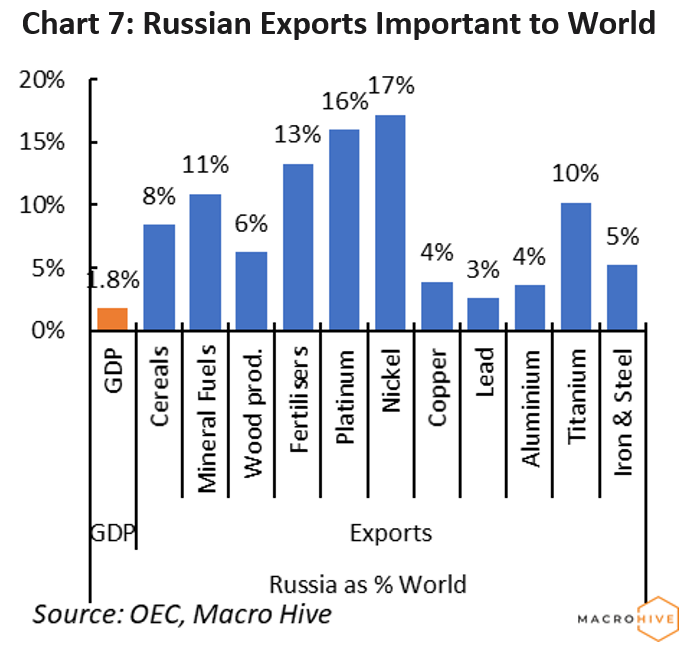

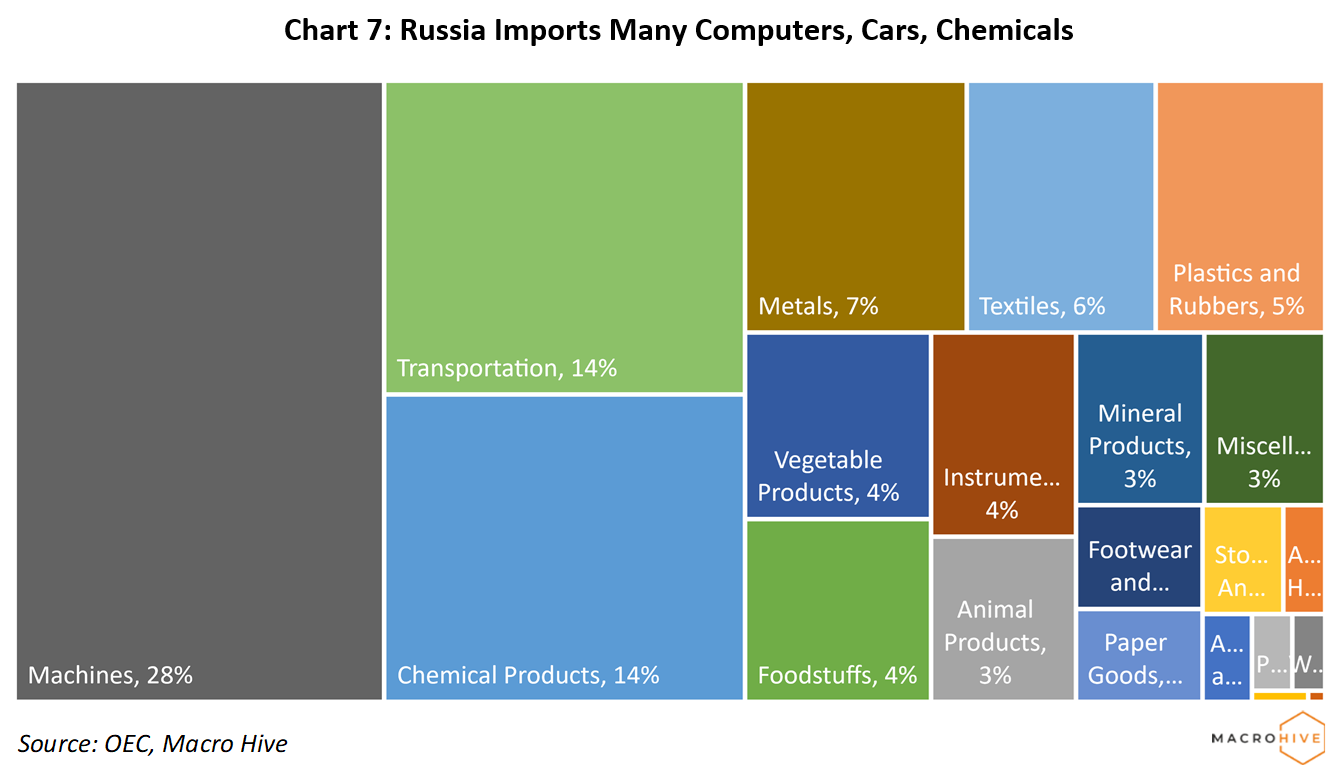

Russia represents only a small fraction of the world economy (1.8%). But it is an important exporter of several products even outside of oil (Chart 7). This means excluding Russia from SWIFT will have an outsized impact on sectors exposed to the raw materials it produces. These include platinum, nickel, titanium and fertilisers.

Curtailing Russian exports will cause sourcing issues for companies and economies who buy from Russia. It will also cause a contraction in sales for companies and economies that sell there. This will have second-round effects. It will hit supply chains across companies even relatively removed from Russia and drive up the price of substitutes.

Further, the political use of SWIFT on a relatively important economy (at least compared to Iran) could shift usage away from SWIFT in the medium term. India and China both have important exposures to Russian exports in their economies (fertilisers, agriculture and energy) and are already looking for ways to mitigate the impact of sanctions.

On this basis, SWIFT removal may hasten the move to adopt new bilateral systems, and with it, lower usage of the US dollar.

Appendix – Russia’s Exports and Imports by Product

Hi Henry – can you please explain why use of platforms other than SWIFT will lower the usage of USD in trade? It is not clear to me as there is nothing about the use of SWIFT that mandates or necessitates the use of USD, is there?

Hi Mark, the thinking is that if foreign alternatives to SWIFT (for instance in China and India) grow in usage in order to sustain access to banks removed from SWIFT, and mitigate the potential future “politicisation” of SWIFT, it will raise their abilities to require settlement in their own currencies going forwards (CIPS is settled in yuan for instance).

I should point out that this is certainly a more medium-to-long-term prospect, as right now the alternatives to SWIFT are relatively underdeveloped and have incredibly low usage by comparison.

Hi Henry, thank you for this explainer I thought that it was mega useful. How will these impact the outlook of USD against other currencies, in particular EM currencies? Does it make it more or less important to EM countries to hold USD?

Hi Erin, glad you liked the piece. It doesn’t have a specific implication for the USD outlook versus other currencies, although Bilal has recently put out his FX view (more details here: https://bit.ly/3sEVPhR)on the back of the risk-off, safe-haven flows that are supporting USD vs EM.

The longer term implications are that it could mean a rise in non-USD denominated trade, which would then in theory mean a lower need for USD holdings for EM countries – however as I say, this would be a much longer-term effect, rather than something you would expect to see immediately.