Economics & Growth | ESG & Climate Change | Europe

Economics & Growth | ESG & Climate Change | Europe

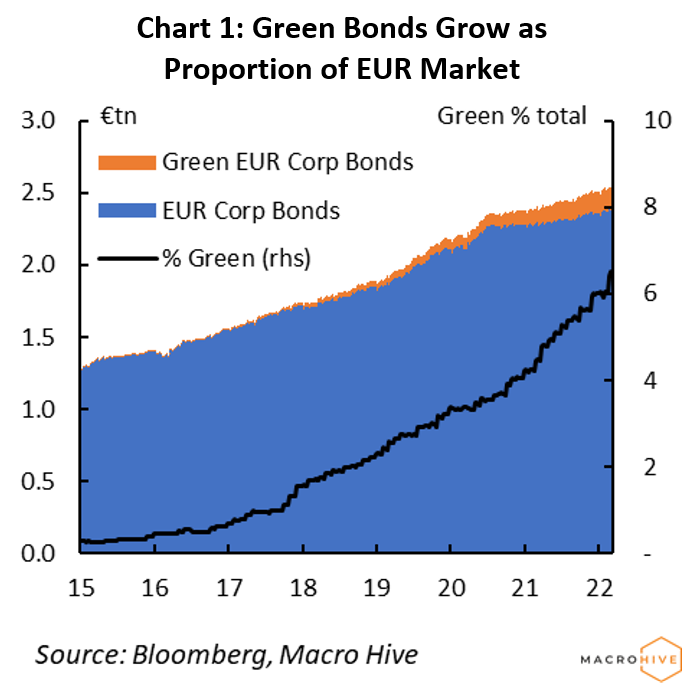

The EU taxonomy (or green taxonomy) arose in response to the issue of greenwashing. So-called green investment and green finance have been growing for several years, gaining traction in the aftermath of the pandemic (Chart 1). However, despite the deluge of assets labelled ‘green’, ‘social’, or ‘sustainable’, the definition of these was often vague (including green bank AT1s and green RCFs) and sometimes non-existent. This is the issue of so-called greenwashing: the posing of activities as greener than they are.

Sustainable bonds come in various forms. The two most common are green bonds and sustainable-linked bonds (SLBs). Green bonds are often self-labelled, and their proceeds are pigeonholed for environmental activities. SLBs are those which include green covenants directly attached to the sustainable credentials of the issuing company.

For SLBs, the covenants are independently verified and easily understood. For example, Enel’s SLB targets direct CO2 emissions and total renewable capacity. By contrast, the definition of what makes a green bond ‘green’ has historically been far vaguer. Here is where the issue of greenwashing raises its head.

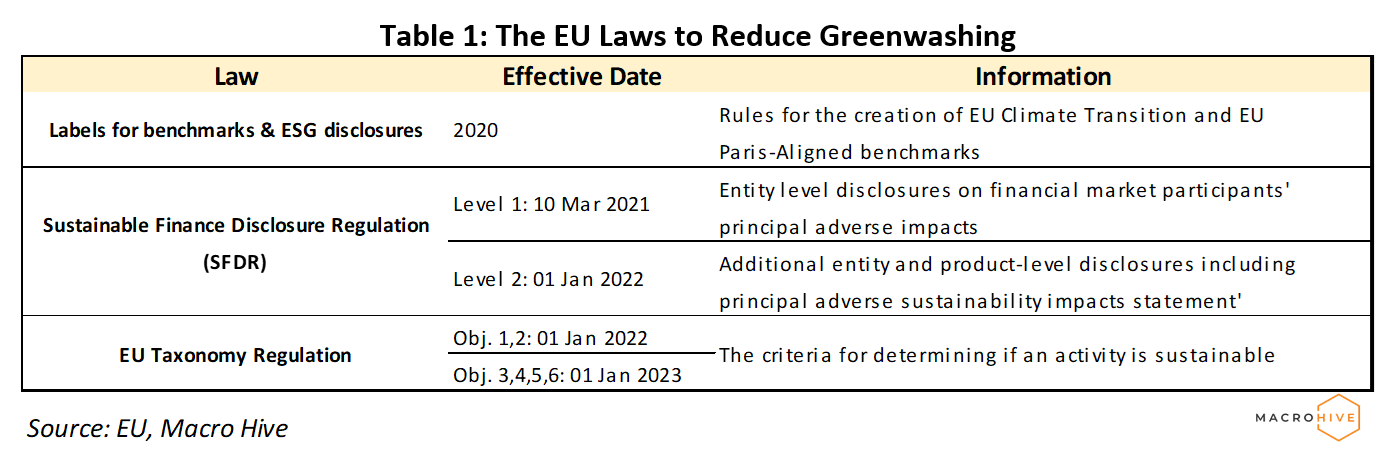

Fighting greenwashing is highly important to the EU. It has committed within its 2019 European Green Deal to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, cutting emissions 55% by 2030. That is estimated to require €260bn in additional annual investment. Ensuring the correct allocation of sustainable investments is therefore key. To this end, in 2020, the EU laid down a framework to increase transparency and counter greenwashing, via several new laws, enforced over a staggered period (Table 1).

The EU taxonomy regulation fits into this framework as the classification system for identifying what entities can label a sustainable activity. It highlights the positive contributing activities so investors (should they wish) can focus there.

The EU taxonomy regulation includes different obligations for different types of economic actors. It distinguishes between those companies with over 500 employees that fall under the non-financial reporting directive (NFRD), financial market participants in the EU, and the EU and its member states for policy setting. NFRD-covered companies will, from 1 January 2022, need to disclose the proportion of revenue, cap-ex, and op-ex (with rationale) that fall under the sustainable umbrella.

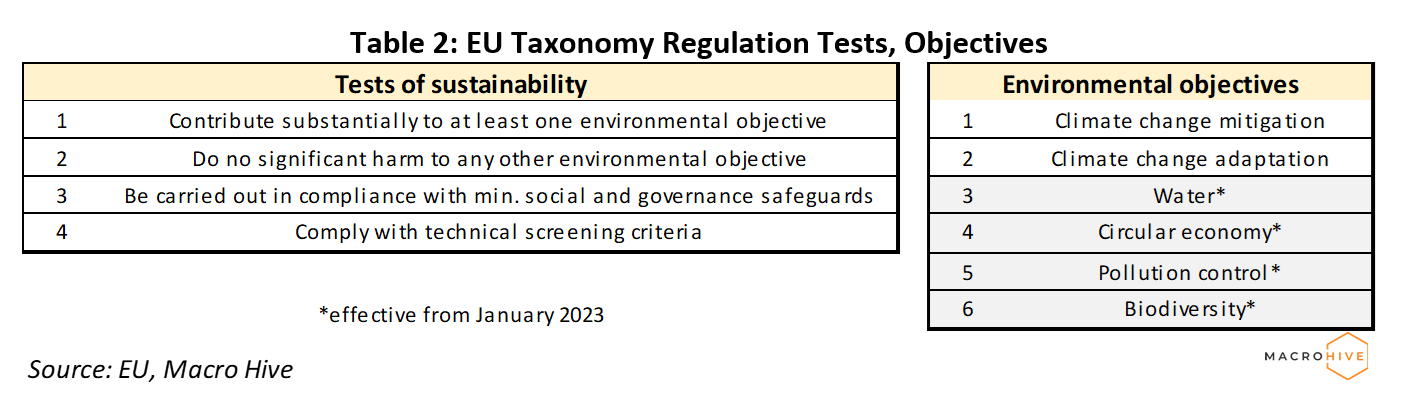

To fall under the definition of sustainability, the EU set out four tests and six environmental objectives (Table 2).

As per Test 4, a critical piece of the EU taxonomy regulation is the Technical Screening Criteria (TSC). This is the information defining when an activity is ‘taxonomy aligned’ and so deemed sustainable. The criteria itself relates to the environmental impact of either the end product (e.g., electric cars) or the production process of that end product (e.g., renewable energy).

The EU approved the first draft of the TSC in principle on 21 April 2021 and adopted it on 4 June 2021. At that time, however, it omitted views on the potential treatment of nuclear and gas. It eventually included them in a (Complementary Climate) Delegated Act on 2 February 2022.

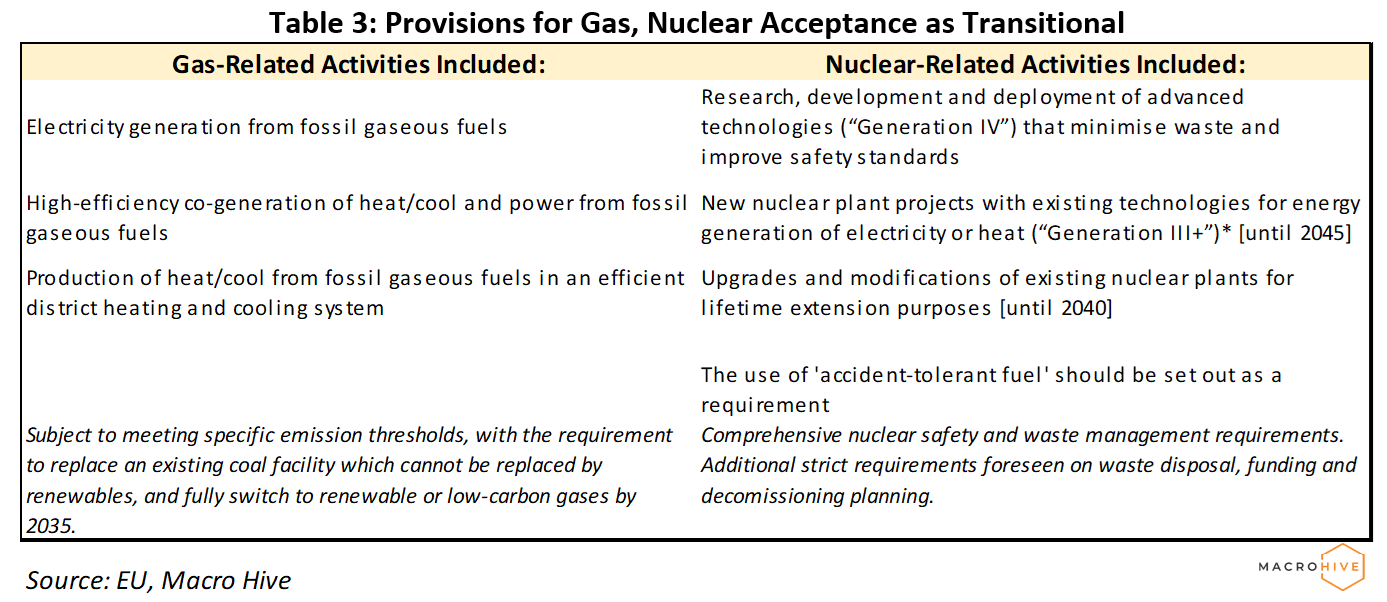

The Delegated Act accepted both nuclear and natural gas activities within the EU green taxonomy subject to several provisions (Table 3). The rationale for their inclusion was that gas is far less carbon intensive than coal (which it generally replaces), while nuclear is carbon neutral and plays an important role in providing a stable baseload energy supply.

The decision has driven various responses and suffered criticism as overly political. France was a big proponent of including nuclear energy (given it generates 70% of its electricity), while Germany has pushed for the inclusion of gas. By contrast, Austria and Luxembourg (both have Green Party members in their governments) have been outspokenly critical of the situation and threatened to challenge it in the EU courts. Environmental activists more generally have disparaged it as lowering climate standards.

Criticisms have also come from pro-nuclear groups including Foratom (the European Nuclear trade body). The requirement that powerplants apply ‘best-available technology’ by their interpretations would preclude all existing nuclear plants. Furthermore, such groups highlight the need to make ‘accident-tolerant nuclear fuel’ available from 2025 as a blocker to practical inclusion. Such fuels are currently at the research stage, making certification and approval by 2025 unlikely.

Following the Delegated Act’s publication, the European Parliament and European Council will have four to six months to scrutinize and decide whether to object to it. The bar for rejection is quite high. It requires a reinforced qualified majority (72% of member states, representing 65% of the EU population) of the Council or a simple majority of the European Parliament.

Assuming the Delegated Act is not rejected, it will come into force from 1 January 2023.

The EU taxonomy’s main aim was fighting the risk of greenwashing. This should remain the main takeaway, despite arguments that the various lobbying groups have diluted it.

The taxonomy is, to a large degree, purely informational. Investment firms face no additional requirements to invest in companies with taxonomy-aligned activities. Nor are companies required to steer more towards such activities. Equally, green investment funds can still choose to reject investment in activities deemed sustainable by the taxonomy with which they disagree.

Practically, the clarification of sustainable activities by companies and the additional disclosures required for investment firms and banks will support the direction of investor money into more sustainable businesses and assets. This should allow a growing premium (greenium) to emerge in favour of such assets. In turn, this should encourage businesses to commit more to sustainable economic activities.

The EU is first to the mark with this. Yet there are already reports of similar work underway across Canada, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, and the UK. To further assist with cross-border cooperation, the EU and China have worked together in their Common Ground Taxonomy to help compare the two regions’ taxonomies.

Spring sale - Prime Membership only £3 for 3 months! Get trade ideas and macro insights now

Your subscription has been successfully canceled.

Discount Applied - Your subscription has now updated with Coupon and from next payment Discount will be applied.