Summary

- Peaking shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, fertilizer prices have since dropped two-thirds and are now only 20% above pre-pandemic levels.

- The global economy has remarkably adjusted to the war’s dislocations, by finding new input sources and in building new production facilities.

- Russia and Belarus are pushing to lift sanctions affecting their ability to export fertilizer products. If successful, that would cut fertilizer prices further.

- Given the likelihood that fertilizer will remain in the headlines in coming months, we explain how fertilizer is made, how it trades in the global marketplace, and how it affects food prices.

Market Implications

- Food prices remain relatively high, but cheaper fertilizer could lead to lower food prices, as farmers plant more crops and improve yields.

Why Are Fertilizer Prices Falling?

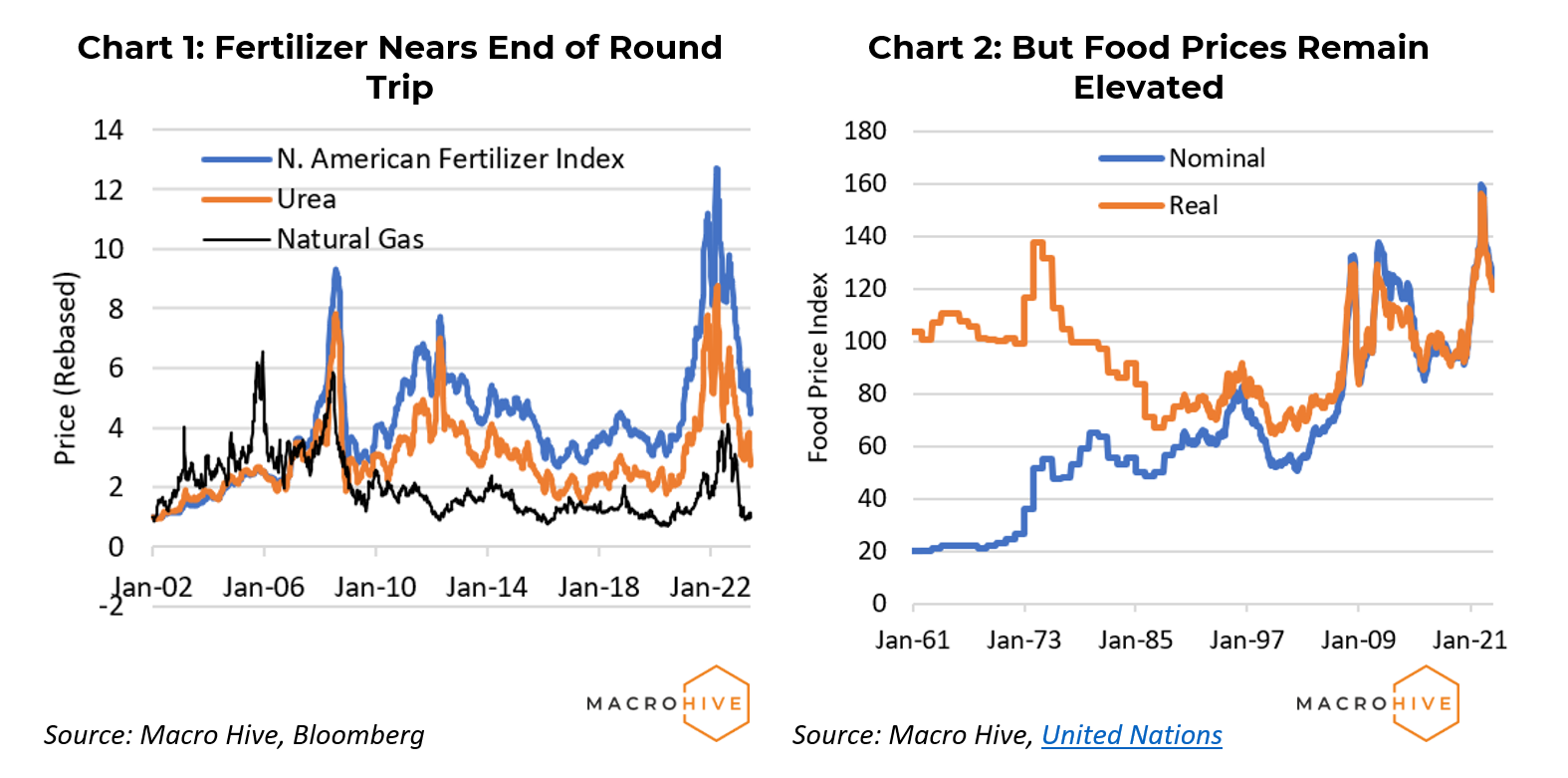

Even as the Russia-Ukraine war rages on, fertilizer prices have collapsed in recent months (in defiance of expectations a year ago). Fertilizer prices had risen significantly after the pandemic hit due to many disruptions in the global economy – then jumped to more than triple pre-Covid levels as the war started. Fertilizer has since dropped two-thirds – but is still 20% higher than late-2019 levels (Chart 1).

There are various reasons for this sharp decline. Chief among them is that raw material inputs – including natural gas, urea, and ammonia – are considerably cheaper. We discuss the role and global marketplace for fertilizer and related raw materials in detail below.

Another lesser-known factor is that Western countries did not outright sanction Russian or Belarussian agricultural products, so they have continued exporting fertilizers over the past year (albeit with more difficulty due to sanctions on financial transactions and access to transportation facilities). For example, Lithuania banned rail shipments of Belarussian potash to the European Union.

Russia and Belarus are reportedly pushing for relief on sanctions that hurt their fertilizer exports. If successful, that would likely result in further declines in fertilizer prices. There is a broad desire to keep food prices down and supplies flowing, especially for less affluent countries. This faces strong opposition from many Eastern European countries.

However this is resolved, the sharp decline in fertilizer prices is testimony to the remarkable ability of the global economy to adjust to dislocations caused by the war. This includes finding new sources of natural gas (e.g., via liquid natural gas tankers) and other raw materials and building new production facilities around the world.

Why Are Food Prices Still High?

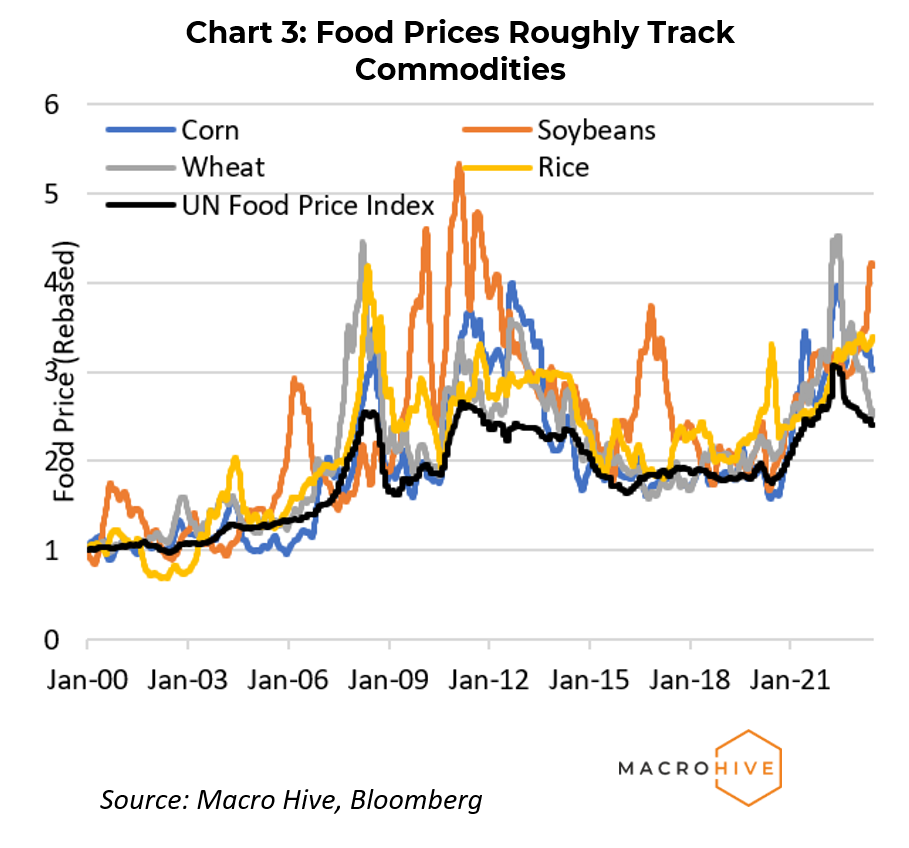

Unlike fertilizer prices, food prices remain elevated (Chart 2). They are down 25% from peak levels in the months after the Russian invasion but still near the highs of the past 60 years. We see several reasons for this.

- High fertilizer prices last year caused farmers to use less of it, reducing yields.

- Farmers have faced other higher costs due to labour shortages and supply chain issues.

- Many countries imposed export controls on their agricultural output after the Russian invasion to protect their food supply.

- Weather disruptions have affected harvests.

Food commodity inputs also remain elevated (Chart 3). The Russian invasion sent corn and particularly wheat prices soaring. Since then, wheat and corn have recovered somewhat although are still considerably higher than pre-Covid levels. At this point, rice and soybeans are the primary pressure points. Dry weather in the US has hurt soybean yields, and floods and harsh weather have reduced rice yields in China and Pakistan.

Relief in 2023? It is possible that at least some food prices will ease further in coming months. Supply chain problems have eased, which should make it easier to obtain raw materials and deliver crops to market. In addition, it is an El Niño year, which will likely affect harvests. Historically, El Niño has resulted in more rain and better harvests in the Americas. But it has also caused drier weather in Asia and Africa, hurting harvests of crops such as palm oil and rice, and wheat in Australia.

That said, cheaper fertilizer will also allow farmers to increase their farming acreage and yields. Given that prospect, this primer describes how fertilizer is made, drivers of fertilizer prices, and how fertilizer fits into the global food economy.

Fertilizer Price Affects Production Costs

Fertilizer is a major cost for farmers. As we discuss below, corn, wheat, and rice require nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizers. Historically, fertilizer has accounted for about 35% of production costs of corn and wheat, and about 15-20% for rice. Soybean production costs are lower at about 10% because they do not require nitrogen-based fertilizer. Soybeans are legumes (e.g., beans, peanuts). Unlike other crops, they can fix or convert atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form naturally.

What Is Fertilizer Anyway?

Fertilizer provides key nutrients to plants and agricultural commodities that may be lacking in the soil. There are two basic types.

Organic fertilizer comes from organic material, including compost, bone meal, manure, and animal waste from food processing plants. It accounts for roughly one-third of total fertilizer shipments. Organic fertilizers nourish the soil and provide natural plant nutrients, but in relatively small doses.

Inorganic fertilizer is made from minerals or various inorganic compounds, and provides three key plant nutrients – nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. These are often only available in the soil in trace amounts. Inorganic fertilizers provide concentrated applications of required minerals. We focus on inorganic fertilizers in this primer.

Why Do Plants Need These Minerals?

Nitrogen

All living organisms require nitrogen. Among other things, nitrogen helps make amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, DNA, and RNA. In plants, it is essential for leaf development and making enzymes and chlorophyll that enable photosynthesis. Even though nitrogen is plentiful, making up 78% of the atmosphere, most plants cannot use it in this form. It must be ‘fixed’ into a compound with hydrogen. We discuss this process below.

Without sufficient nitrogen, plant growth is slow, water use is inefficient, and agricultural yields are low.

Phosphorus

Plants need phosphorus to support stem growth, root systems, flowers, and seeds, and for disease resistance.

Potassium

Potassium is essential for photosynthesis. It regulates the stomata (or openings) in leaves that allow water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide to pass in and out of the plant. Potassium deficiency may cause necrosis (weak or dead spots), brown-spotting, and higher risk of attracting pathogens.

These minerals are often abbreviated as N, P, and K, respectively. They account for roughly 50%, 30%, and 20% of inorganic fertilizers applied to agricultural crops. Wheat and corn each consume about 18% of total nitrogen-based fertilizers globally, with an additional 15% going to rice.

How Are Inorganic Fertilizers Made?

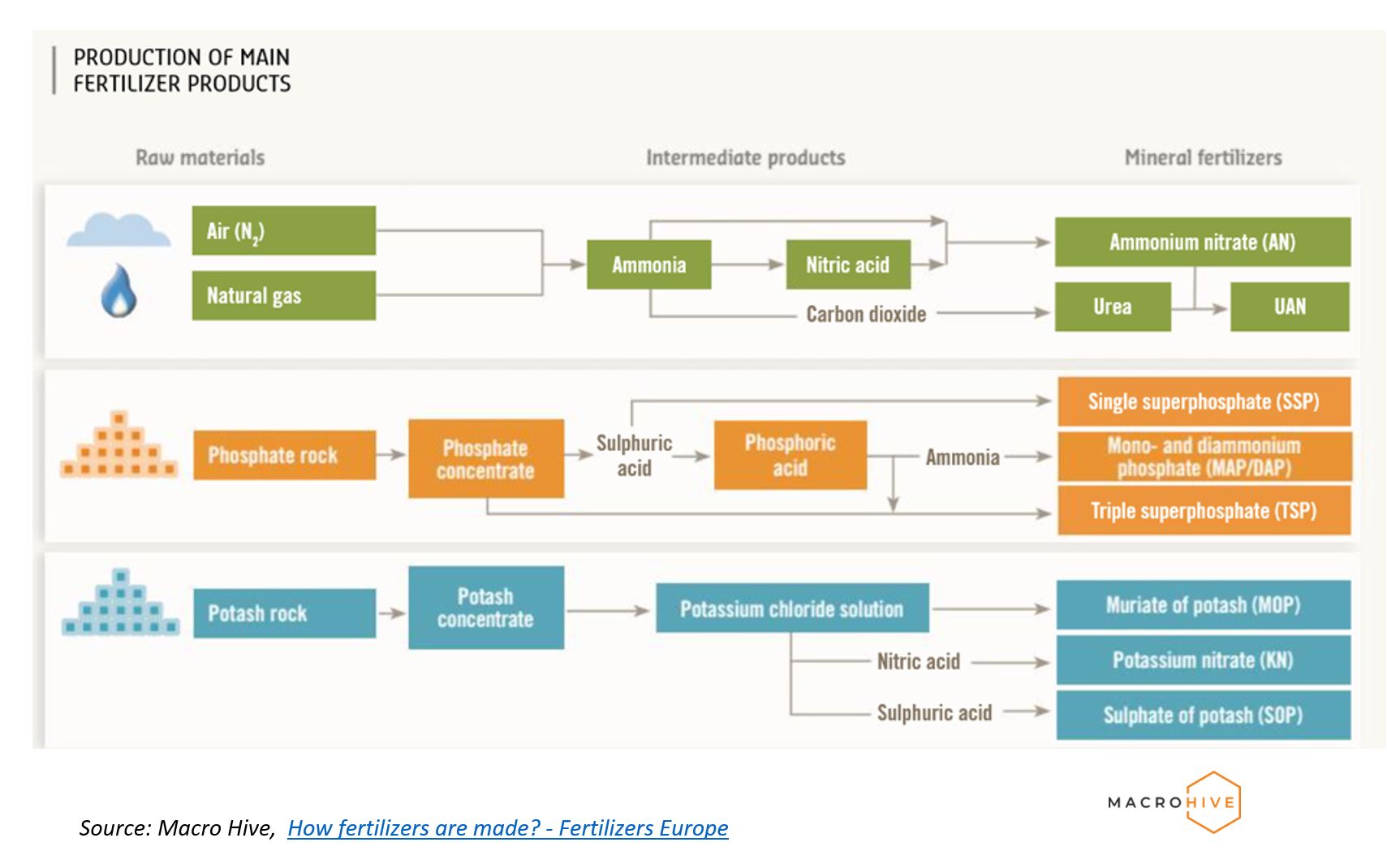

These three types of fertilizers are manufactured in quite different ways, as summarized in the infographic below. Reader alert – as one digs into the process of making fertilizers it soon becomes a series of inorganic chemistry lessons. Hyperlinks are provided for more technical details.

Nitrogen

As noted, nitrogen is plentiful in the atmosphere, but it is not in a form that plants can use. Nitrogen must be ‘fixed’ (or turned into a compound) by combining it with hydrogen and converting it into ammonia via the Haber process. The source of hydrogen is generally natural gas. Ammonia is then either converted into nitrate acid by combining it with atmospheric oxygen, or converted into urea by combining it with carbon dioxide. These products can then be turned into a variety of nitrogen-based fertilizers to meet various needs.

Natural gas accounts for about 85% of ammonia production costs, which in turn drives nitrogen-based fertilizer prices. About 25% of natural gas production is used to produce fertilizer products.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus fertilizers come from phosphate rock and ore. This is refined into phosphate concentrate, and then combined with sulfuric acid to make phosphoric acid. This is then mixed with ammonia to produce phosphate fertilizers.

Potassium

The key ingredient of potassium fertilizers is potash. It is mined and refined, then combined with either chloride or sulphuric acid to make fertilizers.

The Fertilizer Trade Is a Global Business

The fertilizer market is global. Because of the Russia-Ukraine war, the quality of data for 2022 is limited. We discuss the pre-war fertilizer market, with updates on 2022 where some data is available.

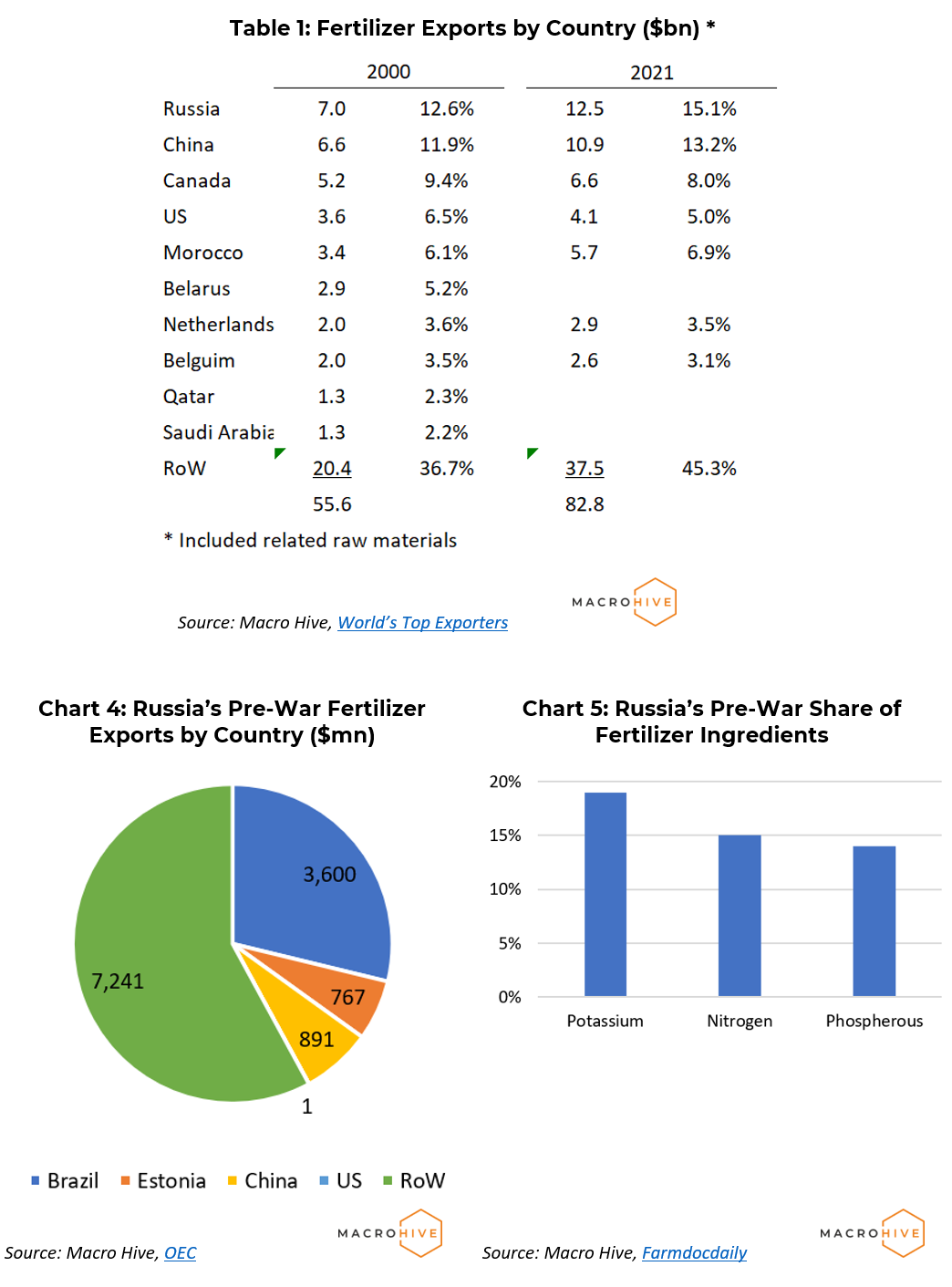

Total global production in 2022 was valued at about $193bn, of which about $70bn is exported by producing countries. The leading exporter in 2020 and 2021 was Russia, with a 12.6% share and 15% share including raw materials (Table 1). In 2022, Canada emerged as the leading exporter, with a total of about $13.7bn – more than double the 2021 level. Canada is a leading producer of potash, which accounts for much of the increase. Russia’s 2022 fertilizer exports are down an estimated 17%.

Before the war, 45% of Russia’s exports went to five countries, with the remainder spread among countries worldwide (Chart 3). Russia was also the leading exporter of fertilizer raw materials, such as ammonia, urea, phosphate, and potash (Chart 4). Russia’s neighbor Belarus was the second largest exporter of potash, with a 20% share. We do not have good data on more recent Russia/Belarus fertilizer exports; the primary message here is that the fertilizer market is global, and many countries are dependent on importing fertilizer.

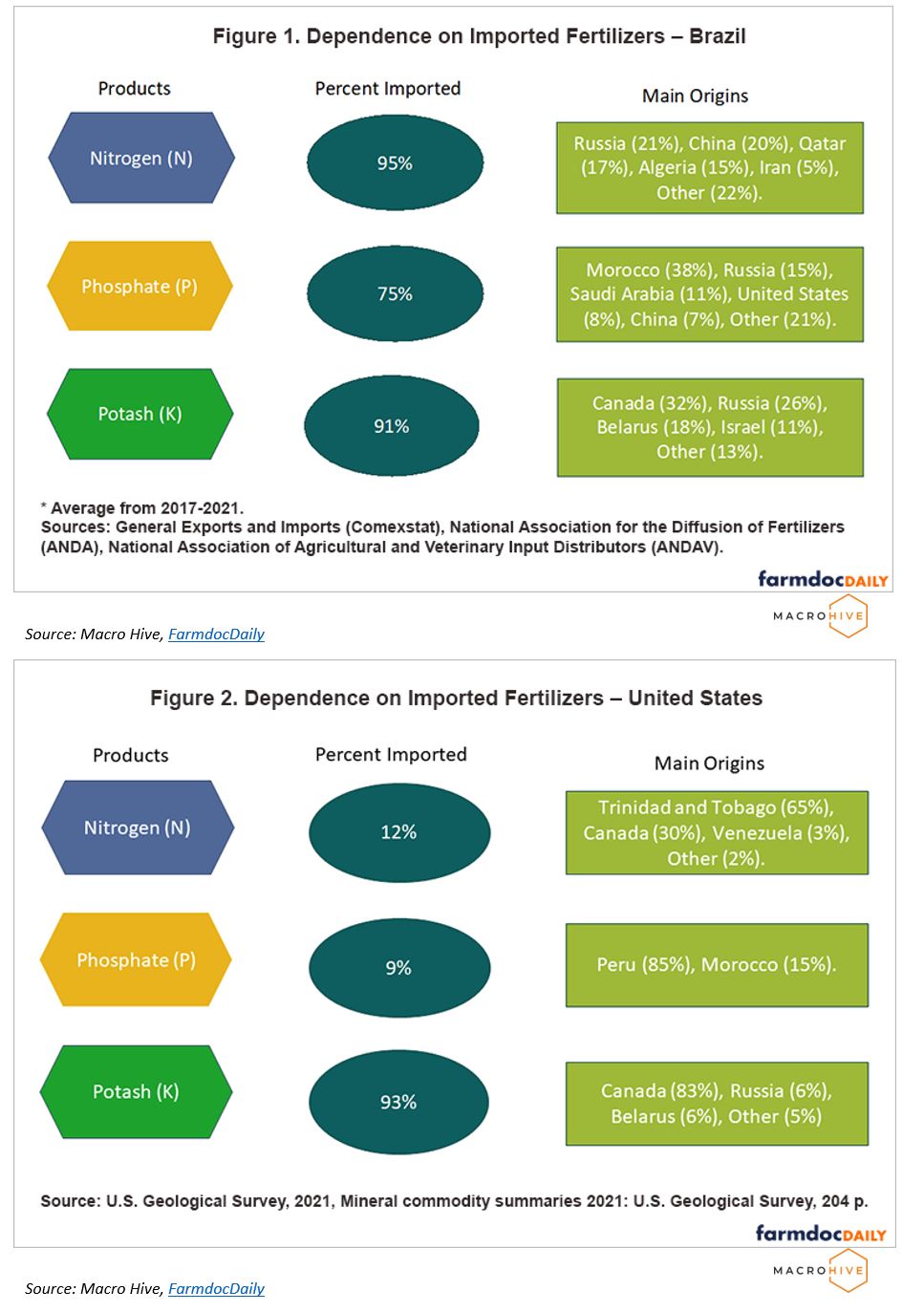

Even though Russia has historically been the largest exporter of fertilizer products, the major importing countries have diversified supply sources. The infographics below summarize where Brazil (Figure 1) and the United States (Figure 2) sourced fertilizer imports, and where they are likely sourcing imports now.

Fertilizers Are Not an Unmitigated Good

Finally, for all the benefits of inorganic fertilizers, they can also be harmful. If they are overused, they can weaken the natural elements of soil, ultimately making it less productive.

Manufacturing inorganic fertilizers is a carbon-intensive process. As the world moves to reduce carbon emissions, new methods of manufacturing fertilizers must be developed.

These twin needs – making fertilizers that better support the soil and are less carbon intensive – will likely keep upward pressure on fertilizers prices over time. But that is a story for another time.

It Is All About Food Prices

Our topic is fertilizer prices, not food prices. But the fact remains that what most people around the world notice is food prices, not fertilizer prices. Food is as ubiquitous a human requirement as energy. Most people in the developed world can cope with higher food prices. But that is less than 20% of the global population. More than half of the world population depends on rice, and lives in a developing country. They have limited means to cope with sharply higher food prices.

We are less concerned about overly expensive fertilizer prices than a year ago. But we also expect fertilizer (and the related global market) to be a hot-button-issue for the foreseeable future.

FAQs

What is the outlook for fertilizer prices?

Fertilizer prices have fallen sharply as the global economy has found new supplies of natural gas and minerals to replace imports from Russia and Belarus. Canada, for example, has significantly increased exports of potash, a key ingredient in nitrogen-based fertilizers.

Some sanctions could be modified so that Russia and Belarus can resume more normal export activity. That would exert further downward pressure on fertilizer prices.

Why are food prices still high?

Last year, when fertilizer was near peak levels, farmers used less of it and planted less acreage. That led to smaller yields and harvests. This year the cost of fertilizer is less constraining, allowing farmers to plant more acreage and boost yields. As these larger harvests come to market food prices may fall further.

In addition, farmers face a variety of other costs, including labour, seed, fuel, and transportation, which may fall more slowly than fertilizer prices.

What does El Niño mean for food prices?

El Niño tends to result in more rain in much of the Americas, and more robust harvests. But it also means less rain in Asia, Australia, and lower Africa, which hurts harvests in those regions.

But harvests in different regions are also subject to weather patterns, climate change, and global warming, which will affect growing conditions positively and negatively.

Very good article, congrat and hope the war end quickly …